Overview

There are approximately 200,000 truck drivers in Australia, representing transport, postal, warehousing; construction; electricity, gas, water, and waste services; manufacturing; mining; and wholesale trade industries (Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations [ANZSCO], 2022). By state, employment rates of truck drivers are highest in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania, Northern Territory, and Australian Capital Territory (ANZSCO, 2022). Truck driving was also reported as the most common occupation among male Australians in 2020, employing one in every thirty‑three male workers or 3% of the national male labour force (Xia et al. 2020). It is therefore critical to the national productivity and welfare of Australia.

Occupational risk

Truck drivers have a 13-fold higher risk of fatal injury than other workers with fatalities primarily occurring from vehicle crashes (Xia et al. 2020). In the 12 months prior to June 2022, 187 people died in crashes involving heavy trucks (Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, 2022). These included 94 deaths in crashes involving articulated trucks and 96 deaths in crashes involving heavy rigid trucks. Compared to last year, fatalities in crashes involving heavy trucks increased by 16.1%, and 9.8% on average over the last three years. It is not surprising therefore that Australian research into truck driver health has focused almost exclusively on safety, including crashes, near misses, fatalities, and traumatic injury (Xia et al. 2020).

How do we understand fatigue?

In biological research, there are many methods of obtaining physiological and neurological data, for example, electroencephalography (Lal & Craig, 2002). This works by attaching electrodes to the scalp to detect electrical impulses generated in brain cells, which tells us about which part of the brain is being activated during different activities, such as driving while tired. Shift workers, for example, also have disruptions to sleep and circadian rhythms, which work on a 24-hour clock. This leads to reduced waking alertness, impaired performance, worsened mood, and fatigue. ‘Mental fatigue’ has also been identified as a phenomenon that occurs from driving for a sustained period. It is associated with increased physical fatigue, reduced productivity, and altered cardiovascular and neurophysiological functionality.

How do we understand the law and what does it mean for drivers?

Regulatory systems play an important role in driver safety outcomes, and Australian truck driver safety generally compares poorly to the United States and other Western countries (Thornthwaite and O’Neil, 2018). For example, in the U.S., drivers must be audited within 18 months of commencing work, and regulation of driver working hours are more stringent with hours-of-service limits being significantly lower. Accreditation, safety ratings and compliance are also made publicly available in the United States.

There are also strong links between working hours, renumeration methods, driver safety, and performance-based systems which incentivise long working hours (Thornthwaite and O’Neil, 2018). These have been found to lead to excessive driving hours, speeding and dangerous driving, and drug use.

Despite these links, only 6.2% of 559 drivers are paid a flat rate per day or week, with most being paid job-based rates and hourly-based rates, or by kilometres driven. Further, 82% of drivers work more than 50 hours per week, and 40% of these drivers reported working more than 60 hours per week. Owner drivers contracting across multiple companies are more likely to work part-time. Almost half of employee drivers reported working moderate to considerable overtime (41-60 hours per week, closer to 60 in most cases), and owner drivers were more likely to report excessive hours (61-80 hours per week).

A substantial number of drivers have expressed scepticism about the efficacy of regulation as it relates to fatigue and rest breaks (Thornwaite and O’Neil, 2018). Some drivers were openly supportive of the need to address fatigue by regulating driving hours, with 66% of drivers perceiving a ‘likely to very likely’ association between injuries and inadequate rest times and breaks, although some also expressed a concern for the lack of rest stops and facilities, and the poor quality of available rest stops.

The health of Australian truck drivers

Between 2004-20015, there were 120,742 accepted workers compensation claims lodged by truck drivers (Xia et al. 2020). Musculoskeletal injury was the most common type of injury associated with these claims.

The health profile of Australian truck drivers compares poorly with the general Australian population (van Vreden et al. 2022). Truck drivers are more likely to be overweight, in poor general health, and have diagnoses of multiple chronic health conditions. Long haul drivers are more likely to experience chronic pain and high levels of psychological stress, particularly those under the age of 35. Long‑haul drivers may be exposed to multiple risk factors such as long working hours, sedentary roles, poor access to nutritious food, social isolation, shift work, time pressure, low levels of job control, and fatigue (Xia et al. 2020).

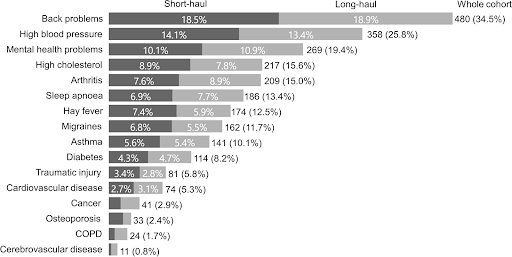

Among 1,390 Australian long haul (>500 km per day) and short haul (<500 km per day) truck drivers (van Vreden et al. 2022):

- 25.2% were classified as either overweight or obese (54.3%), with long-haul drivers being more likely to be obese.

- 29.5% reported chronic health conditions and poor general health (29.9%), including back problems (34.5%), high blood pressure (25.8%) and mental health problems (19.4%).

- 44% of drivers reported chronic pain, particularly long-haul drivers.

- 13.3 and 36.7% experienced severe or moderate levels of psychological distress, more so in short-haul drivers, and younger drivers.

From Xia and colleagues (2021):

- Over 20% of drivers performed work tasks that place them at high risk for injury, such as repetitive movements, manually lifting and working in awkward postures.

- Drivers described frequent exposure to poor work environments such as unpredictable driving by other motorists and poor road or weather conditions. Nearly 50% of drivers had experienced at least one incident of workplace violence in the past 12 months, with verbal abuse the most common.

- Over two thirds (70%) of drivers did not meet the guidelines for a healthy and balanced diet.

- 48.8% of drivers did meet physical activity guidelines.

- 77.7% of drivers were non-smokers but 40.7% were identified as being at high risk of alcohol misuse.

- 62.1% of drivers experienced fatigue whilst working.

- 11% admitted nodding off or falling asleep while driving in the last year.

- 17.5% were defined as being at high risk of poor sleep with 32.7% of drivers using some form of medication (either over the counter or prescription) to manage either sleep or fatigue.

Final Comments

Better management practices and system-wide accountability are critical for improving health outcomes in drivers. Changes must be addressed at organisational, regulatory and government level. Interventions that focus on individual needs of drivers should be prioritised.

References

Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations. (2022). Truck Drivers. https://labourmarketinsights.gov.au/occupation-profile/drivers-truck?occupationCode=7331

Thornthwaite, L., & O’Neill, S. (2016). Evaluating approaches to regulating WHS in the Australian Road Freight Transport Industry: final report to the Transport Education, Audit and Compliance Health Organisation Ltd (TEACHO). Macquarie University, Centre for Workforce Futures.

Xia, T., Van Vreden, C., Pritchard, E., Newnam, S., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., Lubman, D., Collie, A., de Almeida, A., & Iles, R. (2021). Driving Health Report 8: Determinants of Australian Truck Driver Physical and Mental Health and Driving Performance: Findings from The Telephone Survey. Monash University. https://doi.org/10.26180/16563984

Xia, T., Iles, R., Newnam, S., Lubman, Dan I., & Collie, A. (2020). National Transport and Logistics Industry Health and Wellbeing Study Report No 2: Work-related injury and disease in Australian truck drivers. Monash University. Report. https://doi.org/10.26180/13315940

van Vreden, C., Xia, T., Collie, A., Pritchard, E., Newnam, S., Lubman, D. I., de Almeida Neto, A., & Iles, R. (2022). The physical and mental health of Australian truck drivers: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 464. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12850-5